Have you ever finished a curry puff only to be disappointed that the last bite was just hard pastry with no filling? Have you ever spent a week reading the final installment to a fantasy trilogy only for the main character to die disappointingly due to an idiotic decision? Are you one of those Game of Thrones fans who signed the petition on Change.org to remake the (horrible) final season because the ending was abysmal?

Nothing is more upsetting than a disappointing ending — be it for a favorite TV series, a concluding book, or an afternoon snack. The same goes for speeches.

Why does your speech need a conclusion?

Due to the “Recency Effect” in learning, the audience is more likely to remember the most recent thing a speaker said. To end a speech without a conclusion is akin to disrespecting the audience, who have invested the time to listen in rapt attention for a much-awaited finale. Without a good conclusion, the audience is often left disappointed, unconvinced, or confused. Therefore, the conclusion serves a two-fold purpose: to signal the end of the speech and reinforce the speaker’s message.

DO: give a signal

A good speaker gains credibility as the speech progresses, but ending a speech abruptly — without thought or tact — can severely damage that credibility. Movies use rolling credits to signal the end of a movie. A book has an epilogue to let their readers know of the end. Fairy tales use the age-old line, “And they lived happily ever after…” as a classic way to end a story.

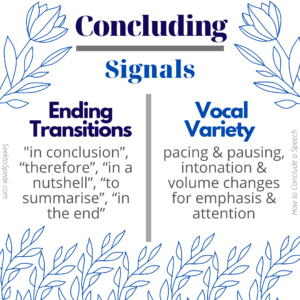

Similarly, with speeches, the appropriate transitions need to be used to signal the end of the speech for the audience to perk up and pay attention. Examples of Ending Transitions include the phrases, “in conclusion”, “in a nutshell”, “to summarise”, “in the end”, or any equivalent words.

Such transitions should also be accompanied by the appropriate Concluding Vocal Variety to clue-in the audience of the finale. This could mean slowing down and pacing your words, taking appropriate pauses for emphasis, using intonation to maintain interest, or speaking louder to ensure attention.

DO: summarise

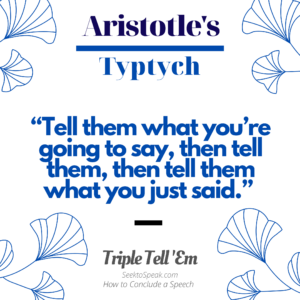

Unlike reading an article or a book where readers are able to reread paragraphs, highlight important points or jot down notes, speeches are often harder to follow and commit to memory. Hence, speakers are often advised to, “Tell them what you’re going to say, then tell them, then tell them what you just said.”

Listeners may have missed something that was said in the first point or were unconvinced by the second point or got confused by the time the third point is made. Reminding the audience and reinforcing your message is important for the audience to think about the points you made — long after you’ve concluded your speech.

Without sounding repetitive, a conclusion should succinctly summarise the main points of a speech, emphasizing — in one line — the essence of your speech. The audience should not be forced to piece the points together by memory alone. Please see the example below:

Topic: Vernacular Schools

Goal of speech: To persuade the audience that vernacular schools in Malaysia does more harm than good.

Main Points:

Vernacular schools create a bright-line divide between communities by isolating students of different races and cultures

Vernacular schools fail to equip and expose students to the reality of a multiracial and diverse society

Vernacular schools dilute the spirit of unity and tolerance between different races in the country

Summary of Points in Conclusion: Vernacular schools divide communities, fail to reflect reality, and dilute the spirit of unity and tolerance.

DON’T go overboard

Conclusions should be succinct yet impactful. This means that a conclusion should NOT:

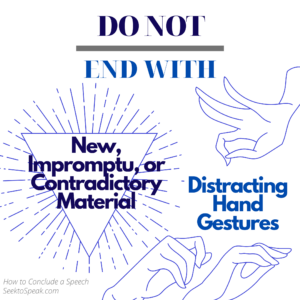

Introduce additional or new material. All your main points should have already been well-explained in the body of your speech. Introducing further points will only confuse the audience, dilute the strength of the new points (as they were introduced last-minute without sufficient analysis) and make the conclusion lengthy and boring.

Include distracting or excessive hand gestures. Most speakers end their speech and conclude as they shift their papers together to leave. Why the rush? You may do all this after you finish the speech. Don’t draw the audience’s attention to the shuffling of your papers or your readiness to leave the stage. This also means you should conclude without overt hand gestures when the speech is tapering to the end. If not, the audience will be more likely to pay attention to the overt hand gestures, instead of your concluding remarks.

DON’T lose focus

Speakers are encouraged not to memorize their speeches word-for-word. However, the exception to this rule would be the speech’s introduction and conclusion — the places where you are most likely to be remembered. Plan your conclusion beforehand. Memorize each word. Practice it regularly. Deliver it with all your energy. Your conclusion must be done with intention. Therefore, your conclusion must not be;

Ad-libbed or improvised. Going impromptu in your conclusion will most likely cause you to ramble and go off-topic. This will confuse your audience and may dilute your speech’s persuasiveness.

Inconsistent with your message. Your conclusion should echo your speech and not appear separate from it – no matter the gambit you want to play for your finale. The audience should not be left guessing about what to believe.